Blog: Profesor Manuel Gurpegui – Catedrático y Director del Departamento de Psiquiatría de la Universidad de Granada.

Fecha: 30-04-2004

Autor:

Manuel Gurpegui

M. Carmen Aguilar

José M. Martínez-Ortega

Francisco J. Díaz

José de León

Descargar PDF:

Abstract

Several studies suggest that caffeine intake is high in patients with schizophrenia and a few of them suggest that caffeine may contribute to schizophrenia symptomatology. None of these studies control for the effect of tobacco smoking, which is associated with induction of caffeine metabolism. Therefore, the high amount of caffeine intake among patients with schizophrenia may be due to their high prevalence of smoking. This is the first large study to explore whether caffeine

intake in patients with schizophrenia is related to tobacco (or alcohol) use or to the severity of schizophrenia symptomatology. The sample included 250 consecutive consenting outpatients with a diagnosis of DSM-IV schizophrenia from Granada, Spain. Fiftynine percent (147/250) of patients consumed caffeine. Current caffeine intake was associated with current smoking and alcohol use. As none of the females used alcohol, the association with alcohol was only present in males with schizophrenia. Among caffeine consumers, smoking was associated with the amount of caffeine intake. Cross-sectional schizophrenia symptomatology was not associated with caffeine intake.

Keywords: Caffeine, coffee, schizophrenia, tobacco smoking, nicotine, alcohol.

Schizophrenia Bulletin, 30(4):935-945,2004.

Caffeine is potentially addictive and is the most widely used psychoactive substance in the world. Caffeine is a competitive adenosin receptor antagonist. Adenosin is a modulator of intracellular signaling that reduces cell excitability. In the central nervous system (CNS), adenosine inhibits the release of acetylcholine, gammaaminobutyric acid (GABA), glutamate, dopamine, norepinephrine, and serotonin. Adenosine Al receptors mediate inhibition of the adenylate cyclase. Adenosine A2 receptors stimulate the adenylate cyclase. Caffeine is an equipotent and nonselective Al and A2 adenosine receptor antagonist. Caffeine releases dopamine (and other amines) in the brain (Benowitz 1990; Donovan and DeVane 2001). Some articles have suggested that selective adenosin agonists may have a role as adjunct therapy in schizophrenia (Ferre 1997; Dixon et al. 1999). Missak (1991) proposed that an endogenous caffeine-like substance may be deficient in schizophrenia.

Caffeine and Schizophrenia

An early review suggested that schizophrenia may be associated with increased use of caffeine (Schneier and Siris 1987). Some early anecdotal reports in institutionalized patients with schizophrenia suggested that some patients were prone to unusual behaviors such as coffee eating (Benson and David 1986; Zaslove et al. 1991Z?) or had exacerbations of their symptoms after increased caffeine intake (Mikkelsen 1978; Hyde 1990; Zaslove et al. 1991b; Kruger 1996). Since institutionalization in other settings, such as prisons, may be associated with an increased caffeine use (Hughes and Bolland 1992; Hughes et al. 1998), it cannot be ruled out that some of these behaviors may be associated with hospital institutionalization.

Polydipsia is also a frequent behavior in severe cases of schizophrenia patients admitted to long-term psychiatric hospitals (de Leon et al. 1994, 1996, 2002a). Polydipsic patients tend to drink high quantities of any liquids and can drink large volumes of caffeinated beverages if they have access to them. A high caffeine intake appears to contribute to the complications of hyponatremia in some polydipsic patients (Kirubakaran 1986). In a 5-year followup of 89 long-term schizophrenia inpatients, Koczapski et al. (1990) found 7 patients with a clear caffeine intoxication (some ate coffee) of whom 3 also had polydipsia with water intoxication. Moreover, water intoxication was only present in the heaviest caffeine consumers.

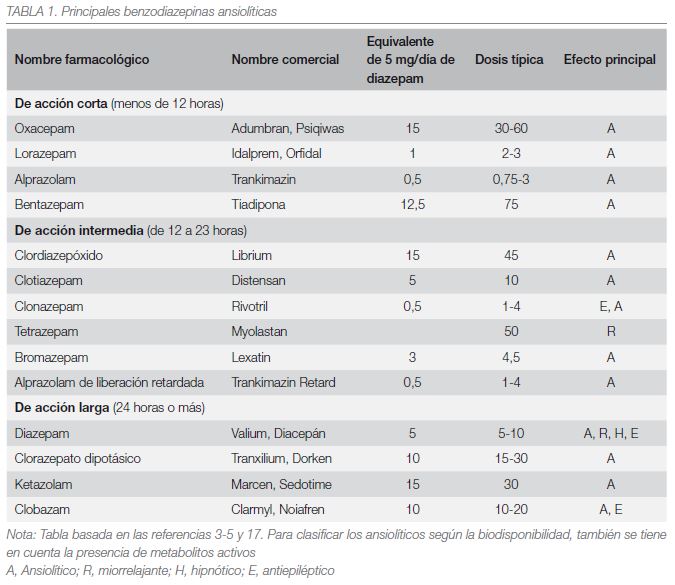

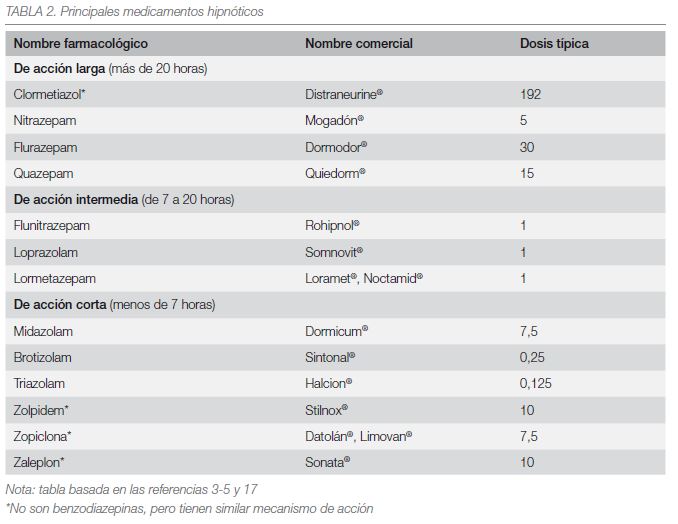

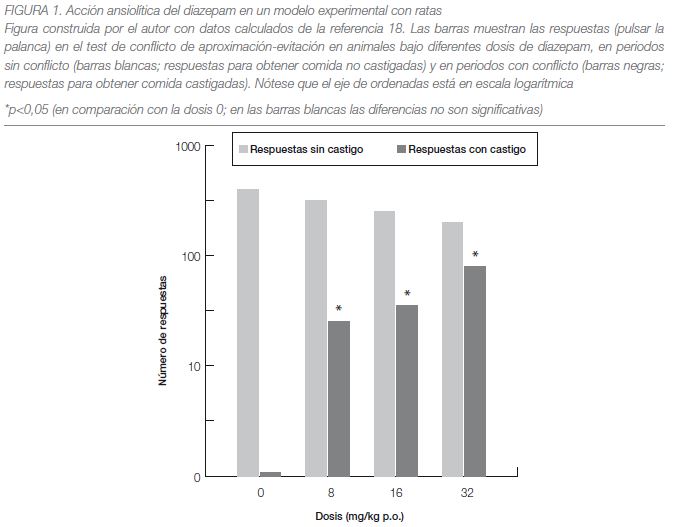

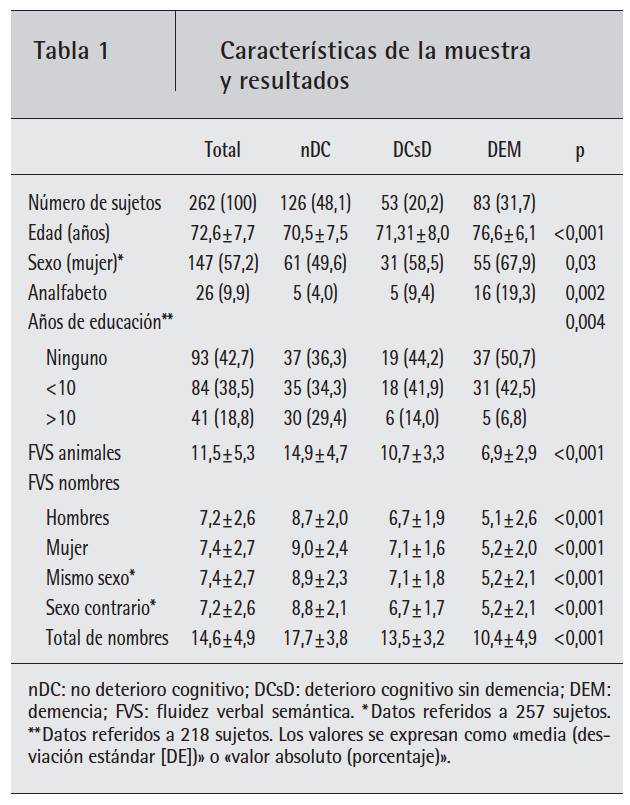

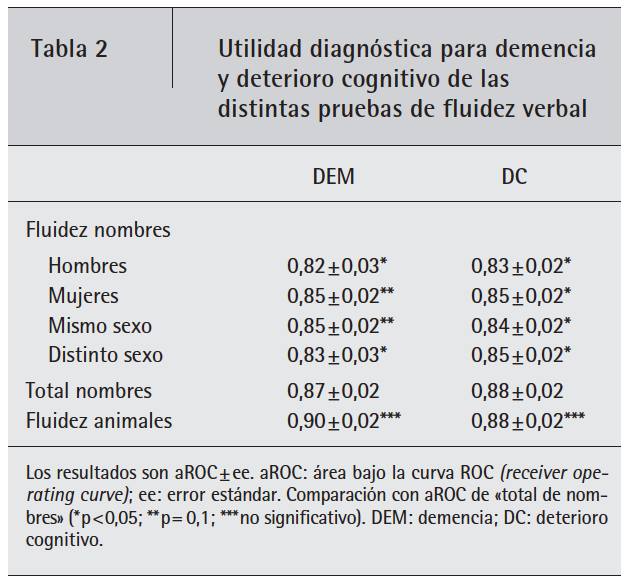

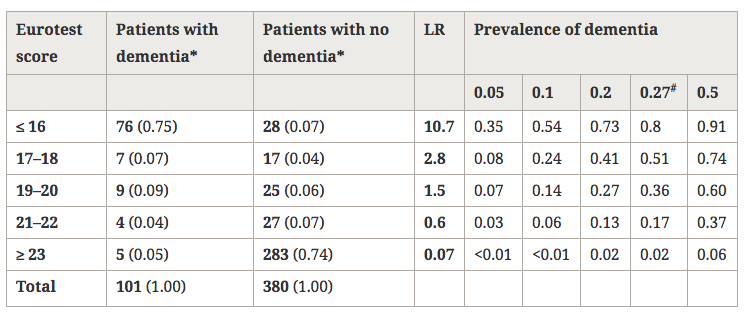

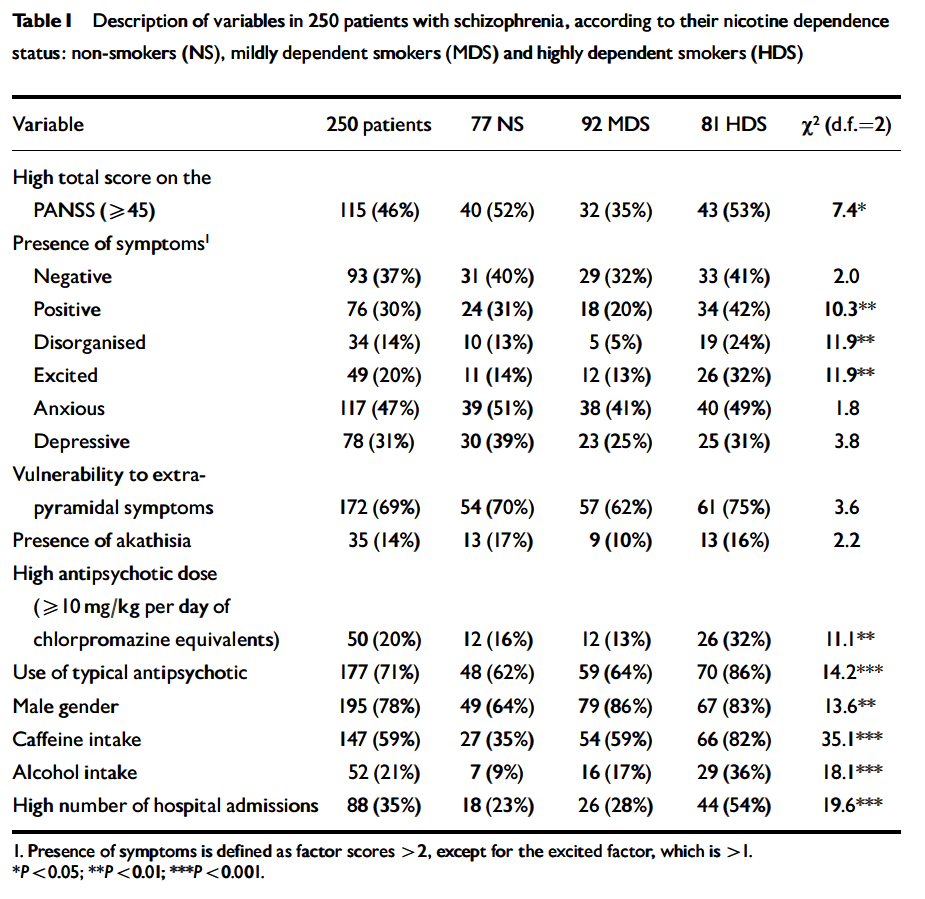

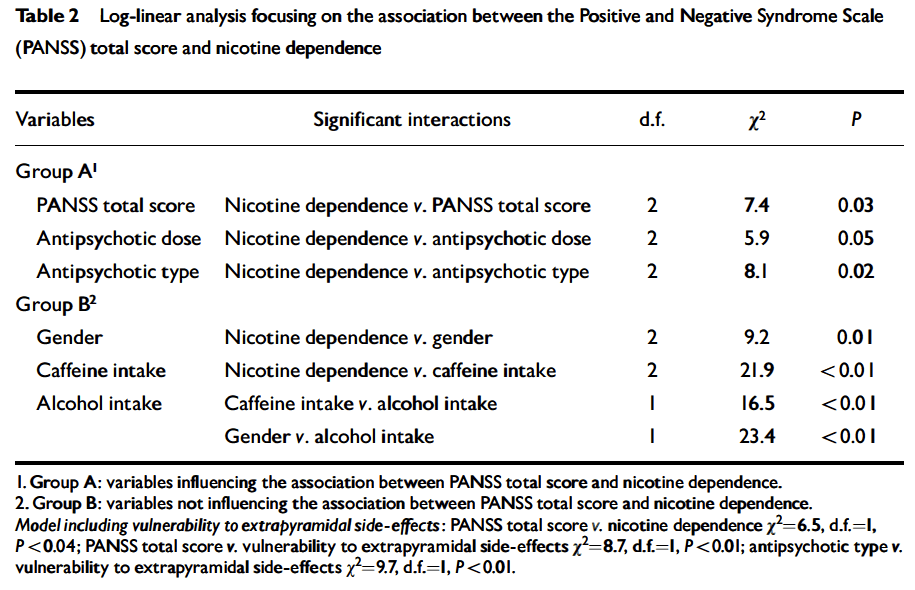

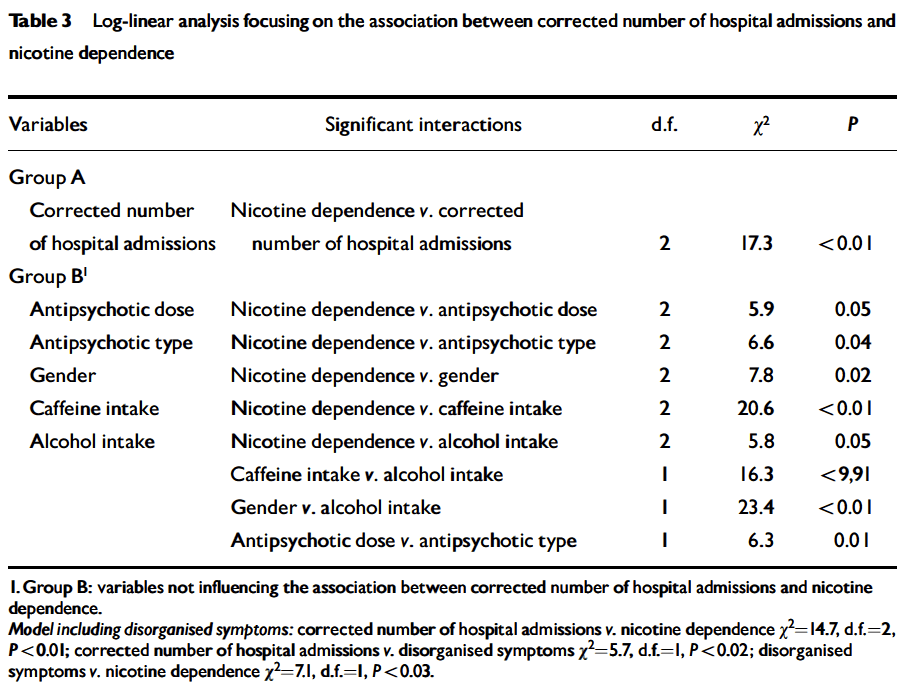

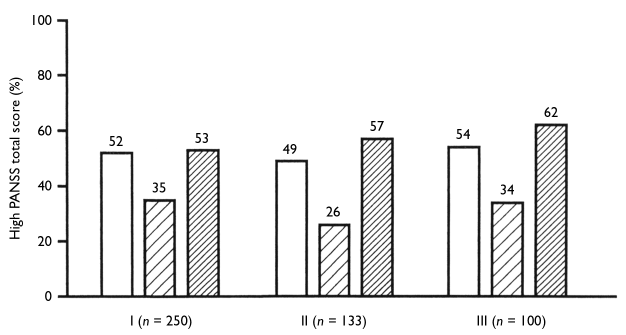

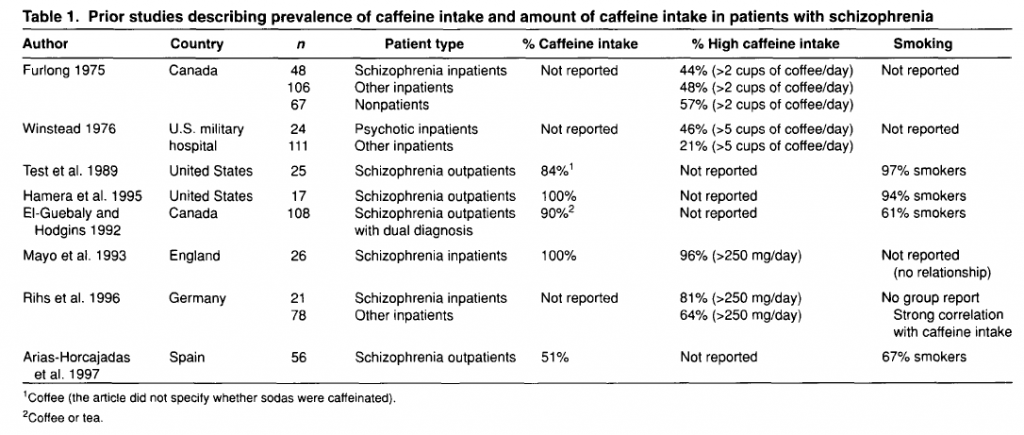

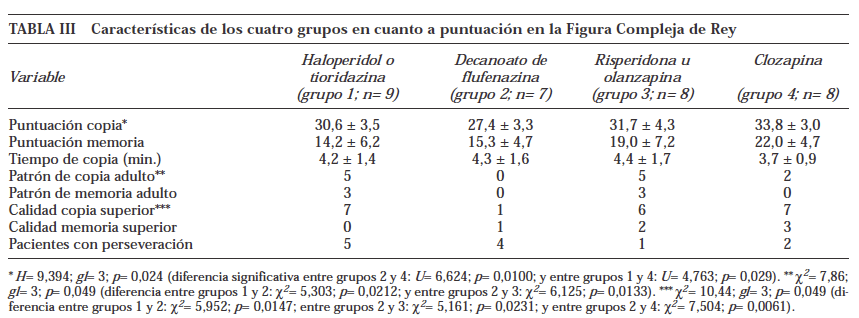

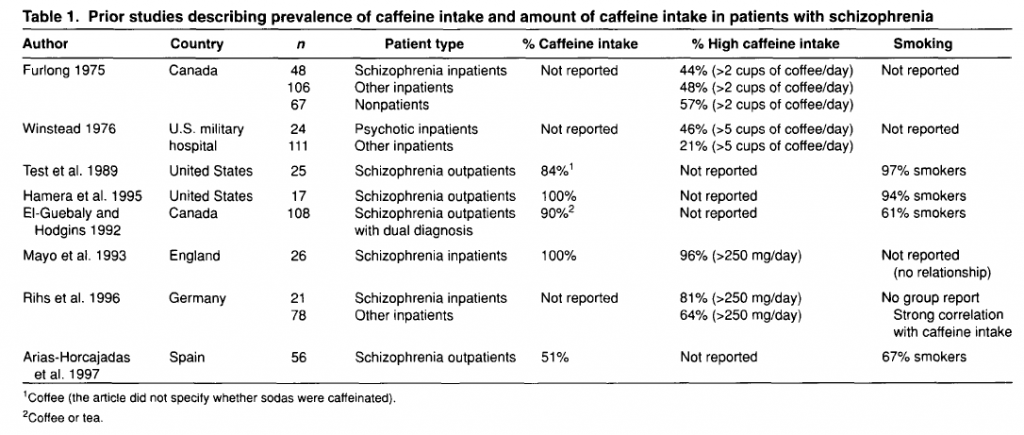

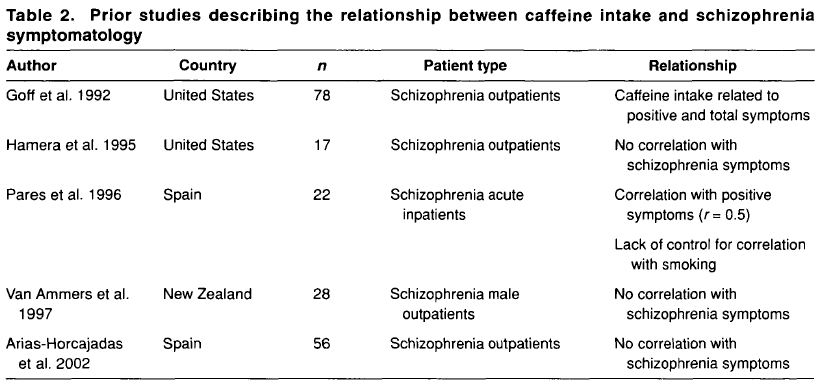

There are several cross-sectional studies suggesting that caffeine intake is high in patients with schizophrenia (table 1) and that caffeine may contribute to schizophrenia symptomatology (table 2). None of these studies control for the effect of tobacco smoking or alcohol drinking. As described below, tobacco smoking is associated with an induction of caffeine metabolism, and smokers tend to need two to three times more caffeine than nonsmokers to reach the same plasma caffeine levels. Therefore, the high amount of caffeine intake noted among schizophrenia patients may be due to their high prevalence of smoking. As a matter of fact, tobacco smoking is very prevalent in schizophrenia patients worldwide. By combining results from eight studies in several countries, it was estimated that the odds for a patient with schizophrenia to be a current smoker was two times higher than the odds for a patient with other severe mental illness (LLerena et al. 2003). There may be a biological association between schizophrenia and tobacco smoking (Freedman et al. 1997; Dalack et al. 1998). Heavy smoking among smokers may be particularly prevalent in schizophrenia patients (de Leon et al. 1995, 2002fc; Olincey et al. 1997). Therefore, when reviewing studies of caffeine intake in the literature, one needs to take into account that the intake of heavy amounts of caffeine by schizophrenia patients may be associated with smoking and its metabolic effects. Similarly, studies relating caffeine intake with schizophrenia symptomatology should correct for the effects of the association between caffeine intake and smoking. Another confounding factor is alcohol intake, which may be associated with caffeine intake.

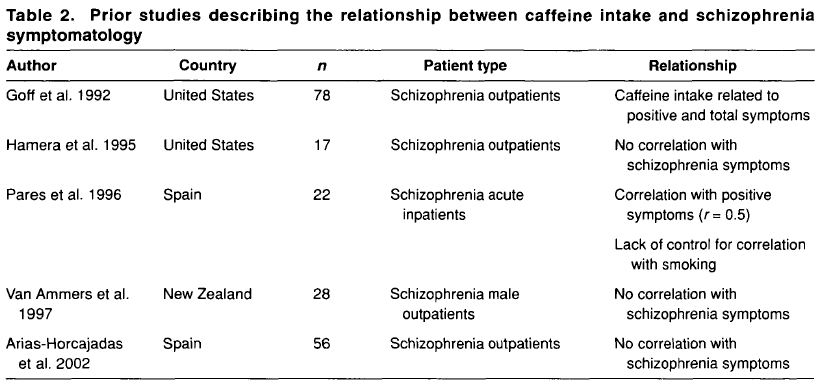

In summary, although there are no systematic caffeine surveys controlling for confounding factors in patients with schizophrenia, the available literature suggests that schizophrenia may be associated with caffeine intake. The presence of high prevalences of alcohol drinkers, smokers, and polydipsic subjects among patients with schizophrenia may contribute to this association. Unfortunately, the literature has not distinguished well whether the association between schizophrenia and caffeine intake means that schizophrenia is associated with a higher prevalence of current caffeine intake, with a higher amount of caffeine intake among caffeine consumers, or with both. The association between caffeine intake and schizophrenia symptomatology has not been well established and published studies do not take into account confounding factors (table 2). On the other hand, caffeine intake may confound biological studies in patients with schizophrenia (Hughes and Howard 1997).

Caffeine and Antipsychotics

Previous studies suggested that typical antipsychotics should not be administered at the same time as coffee or tea because they may precipitate (Hirsch 1979). This precipitation is not explained by the presence of caffeine (Cheeseman and Neal 1981; Lasswell et al. 1984). More importantly, recent studies have suggested that caffeine may cause drug interactions with antipsychotics metabolized by cytochrome P450 1A2 (CYP1A2). Clozapine is also metabolized by CYP1A2, therefore caffeine may increase clozapine levels and contribute to side effects (White and de Leon 1996; Carrillo et al. 1998). Without taking this pharmacokinetic interaction into account, it is difficult to interpret changes in caffeine intake in patients taking clozapine (Marcus and Snyder 1995). In summary, patients and physicians should be aware that caffeinated beverages can decrease the metabolism of CYP1A2- dependent antipsychotics (clozapine and olanzapine).

Caffeine Intake in the General Population

In the United States, where caffeine has been better studied, 85 percent of adults drink coffee, tea, or caffeinated sodas daily (Barone and Roberts 1996; Hughes and Oliveto 1997). A great majority of U.S. subjects may have detectable plasma caffeine levels even foods such as peanuts or chocolate have caffeine (de Leon et al. 2003). In the general population, caffeine intake is weakly related to alcohol intake but is moderately to strongly related to tobacco smoking (Istvan and Matarazzo 1984). This relationship between caffeine, alcohol, and nicotine intake may be partly explained by genetic factors(Hettema et al. 1999). When exploring associations with caffeine intake, it is important to distinguish between current caffeine intake, which is a dichotomous variable (consumed or not consumed currently), and amount of caffeine intake, which is a continuous variable. While the former variable is usually described in a group of people by a prevalence, the latter is described by a mean or a median. Some factors may be associated with only one of these variables, while others may be associated with both of them.

Caffeine and Alcohol Drinking

Alcohol intake appears to be associated with caffeine intake and is therefore a potential confounding factor in caffeine studies (Istvan and Matarazzo 1984; Hughes 1996; Hays et al. 1998). Heavy caffeine intake is associated with heavy alcohol intake, but the relationship appears to be weak (Istvan and Matarazzo 1984). Patients with present and past history of alcohol abuse/dependence report high caffeine intake (Istvan and Matarazzo 1984;

Hughes 1996). Besides this epidemiological information, a few animal studies suggest that caffeine treatment is associated with increases in alcohol consumption. It is possible that caffeine may decrease alcohol’s sedating effects, although there is no agreement on this issue (Hughes 1996). In a study exploring the use of alcohol and caffeine in relation to depressive symptoms, alcoholics did not differ from other psychiatric patients in the use of caffeine (Leibenluft et al. 1993).

Caffeine and Smoking

Smokers have a higher caffeine intake than nonsmokers (Swanson et al. 1994), have plasma caffeine concentrations that are two to three times lower than nonsmokers with the same caffeine intake (de Leon et al. 2003), and have increased plasma caffeine concentrations after smoking cessation (Benowitz et al. 1989). The polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons found in tobacco smoke appear to be inducers of CYP1A2, the caffeine main metabolic pathway (Bertz and Granneman 1997).

In rats, chronic consumption of caffeine accelerates the acquisition of nicotine self-administration, and the exclusión of caffeine from the drinking water of animals maintained on nicotine results in a dramatic response reduction during the first caffeine-free session (Shoaib et al. 1999). Both nicotine and caffeine contribute to psychomotor stimulant effects, but through different neurotransmitter systems. The effects of nicotine appear to be mediated by mesolimbic dopamine systems (Pontieri et al. 1996), whereas the effects of caffeine appear to be mediated by the antagonism of adenosine A2 receptors. The adenosine A2 receptors are located on the same postsynaptic neurons as the D2 dopamine receptors. Adenosin receptors modulate dopaminergic function by regulating dopamine release in presynaptic neurons and intracellular signaling in postsynaptic striatal neurons (Kim and Palmiter 2003). Besides the modulating effects through adenosin receptors, it is posible that caffeine may have some dopamine agonist properties, including agonist actions at D, receptors (Ferre et al. 1991 ;Casasetal. 2000).

In summary, in the general population, smoking is clearly associated with a higher amount of caffeine intake among caffeine drinkers. This may be mainly explained by a pharmacokinetic (metabolic) effect. Current tobacco smoking also appears to be associated with an increased prevalence of current caffeine intake. It is possible that this is related to pharmacodynamic factors (interactions at receptor level) and/or genetic factors.

To conclude this introduction, although there is no agreement on the matter, some cross-sectional studies have suggested that caffeine intake may be associated with schizophrenia symptomatology (table 2). However, the literature provides no systematic surveys of caffeine in patients with schizophrenia controlling for the effects of smoking or alcohol drinking, which are associated with schizophrenia. This current, large study explores whether caffeine intake in patients with schizophrenia is related to the severity of schizophrenia symptomatology, controlling for tobacco and alcohol use. The hypotheses explored in this study are as follows: in patients with schizophrenia, (1) caffeine intake is associated with smoking, (2) caffeine intake is associated with alcohol drinking, and (3) caffeine intake is associated with severity of schizophrenia symptoms. These hypotheses will be explored by using two different variables: current caffeine intake and amount of caffeine intake.

Methods

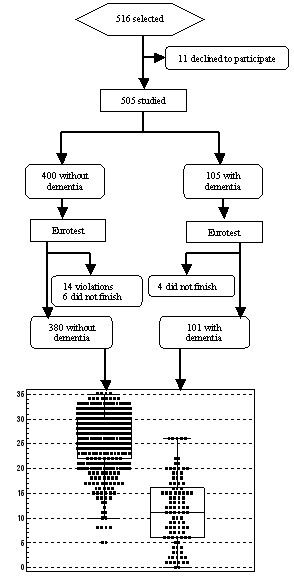

Sample. The location of the study was at the two Community Mental Health Centers and an outpatient rehabilitation program that cover the catchment area of the city of Granada, in the south of Spain. All patients receive free psychiatric treatment from the national health system. The sample included the first 250 consecutive patients with a diagnosis of DSM-IV (APA 1994) schizophrenia who provided written informed consent after a complete description of the study. The diagnosis was made with the clinician version of a structured diagnostic interview (First et al. 1994). During the recruitment process, a total of 278 consecutive patients were considered to participate in the study. Ten of these patients had a chart diagnosis of schizophrenia but did not meet the DSM-IV diagnosis. Therefore, they were excluded from the study by the research psychiatrist. In addition, 18 DSM-IV schizophrenia patients refused to consent. This left us with the 250 patients. All of the patients were Caucasians, like the majority of the Spanish population. The number of hospitalizations, corrected by illness duration, was used as a historical measure of prognosis.

Scales. Schizophrenia symptomatology was assessed with the Spanish version of the Positive and Negative Symptoms Scale (PANSS), which can be used to provide factor scores (Peralta et al. 1994). The Simpson-Angus Neurological Rating Scale (SANRS; Simpson and Angus 1970) and the Barnes Akathisia Scale (BAS; Barnes 1989) were used to measure extrapyramidal side effects. Those patients treated with anticholinergics or those with a score > 0 in either the SANRS or the BAS scales were considered as having a vulnerability to extrapyramidal side effects. Only one rater, a research psychiatrist (M.C.A.) rated all scales in all patients.

Assessment of Substance Use. Heavy smoking among smokers was defined as smoking 1.5 packs or more per day according to patient’s report (de Leon et al. 1995). The frequency of current smoking among all patients and of heavy smoking among smokers was studied. Nicotine dependence was assessed in smokers by using the Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND; Heatherton et al. 1991). Prior studies have found that the FTND has two underlying latent factors: the Smoking Pattern and Morning Smoking factors (Haddock et al. 1999). The Smoking Pattern factor was calculated by adding FTND items 1, 2, 4, and 6. Because the daily number of cigarettes smoked (item 1) loads this factor, it is a measure of nicotine dependence associated with heavy smoking. The Morning Smoking factor was calculated by adding FTND items 3 («hate to give up morning cigarette») and 5 («smoking more in first hours after awaking») and may be a measure of nicotine dependence that is not influenced by heavy smoking and therefore may be independent of the metabolic effects of heavy smoking. The current use of alcohol and illegal drugs was assessed by patient interview and verified by chart review and collateral information from the family. Patients were asked about their consumption of caffeinated beverages. As in U.S. epidemiological surveys, average weekly amount of caffeine intake was determined by estimating caffeine content in caffeinated beverages and then converting it to mg/kg/day Barone and Roberts 1996; Hughes and Oliveto 1997). In this Spanish sample, the standard caffeine content used for coffee was 100 mg in a 150-cc cup of drip coffee (Bedate 1981). This is a little higher than the U.S. standard of 85 mg in a 5-oz cup of brewed coffee (Barone and Roberts 1996; Hughes and Oliveto 1997). Other European studies considered that European cups of coffee have greater amounts of caffeine than U.S. cups (Rihs et al. 1996). In this study, the standard caffeine content used for caffeinated sodas was 23 mg in a 200-cc glass of soda. This is equivalent to the U.S. standard of 40 mg in a 12-oz cup (Hughes and Oliveto 1997). A high amount of caffeine intake was defined as consuming more than two cups of coffee per day or more tan 200 mg of caffeine/day.

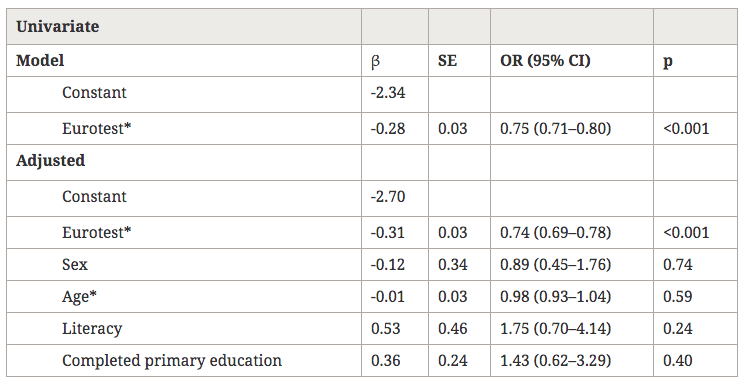

Statistics. The Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS; SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL) was used for calculations. Odds ratios (ORs) were computed from two-way crosstabulations for univariate analyses. The 95 percent confidence intervals (CIs) for ORs were calculated. The presence-absence of current caffeine intake was the dichotomous dependent variable for a logistic regression analysis using several dichotomous independent variables: current smoking, high dose of antipsychotic medication (> 10 mg/kg/day chlorpromazine equivalents), typical antipsychotics, vulnerability to extrapyramidal side effects, high total PANSS score (> 45), age > 35 years, gender, and alcohol use. A similar analysis was performed for a high amount of caffeine intake (> 200 mg/day) among caffeine consumers. All logistic models fit well according to the Hosmer-Lemeshow Goodness-of-Fit test. Caffeine intake across levels of severity of smoking and schizophrenia symptomatology was studied using Kruskal-Wallis tests.

Results

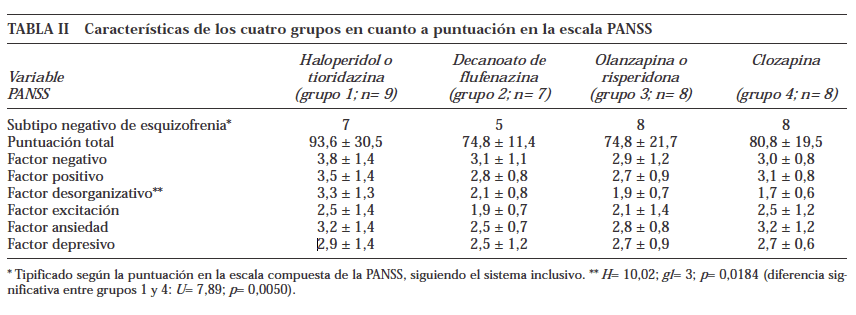

Sample Description. The mean (SD) age was 36.1 (9.5) years, and mean age at diagnosis was 21.9 (6.0). Seventyeight percent (195/250) were males. The mean (SD) PANSS factor scores were 1.8 (0.7) for the negative, 1.6 (0.9) for the positive, 1.3 (0.5) for the disorganized, 1.1 (0.4) for the excited, 1.7 (0.7) for the anxious, and 1.6 (0.5) for the depressive factor. These scores were low and reflected that patients were stable outpatients. In Spain, patients are not discharged from acute admissions until they are doing well and can live in the community (almost always with their family).

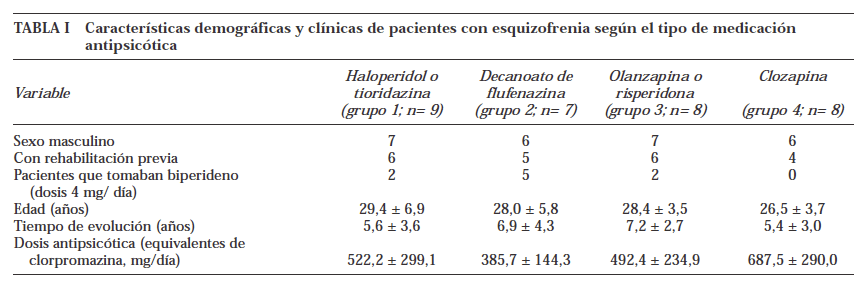

Ninety-four percent (236/250) of patients were taking antipsychotics with a mean (SD) dose of 550 (459) mg/day of chlorpromazine equivalents. Typical antipsychotics were prescribed in 71 percent (177/250) and antiparkinsonians in 37 percent (92/250) of patients. Sixty-nine percent (172/250) of the patients had a vulnerability to extrapyramidal side effects.

The frequency of current smokers was 69 percent (173/250) and the mean (SD) number of packs per day among current smokers was 1.5 (0.7). Heavy smoking was present in 57 percent (98/173) of smokers. Among smokers, the mean (SD) FTND score was 6.8 (2.3). The means (SD) of the Smoking Pattern and Morning Smoking factors were 5.8 (2.0) and 1.0 (0.8), respectively. Current use of alcoho and illegal drugs was present in 21 percent (52/250) and 7 percent (17/250), respectively.

Current Caffeine Intake and Associated Variables in Univariate Analysis. No subjects were consuming tea or over-the-counter medications containing caffeine. Coffee was consumed by 51 percent (127/250) of the patients and caffeinated sodas by 23 percent (58/250). These two percentages overlapped because some patients consumed both types of caffeinated beverages. ifty-nine percent (147/250) consumed at least one type of caffeinated beverage.

Current caffeine intake was reported by 64 percent (125/195) of male and 40 percent (22/55) of female patients. Thus, caffeine intake was significantly associated with male gender (table 3). Current caffeine intake was reported by 69 percent (120/173) of smokers and 35 percent {21 HI) of nonsmokers. Thus, current caffeine intake was significantly associated with current smoking (table 3).

Current caffeine intake was reported by 90 percent (47/52) of alcohol drinkers and 51 percent (100/198) of nondrinkers. Thus, current caffeine intake was significantly associated with current alcohol use (table 3). Current caffeine intake was also significantly associated with treatment using typical antipsychotics (table 3), but vulnerability to extrapyramidal side effects was not significant.

In males, current caffeine intake was present in 36 percent of nonsmokers who did not consume alcohol and in 62 percent of smokers who did not consume alcohol (X2 = 8.5, df= 1, p = 0.004). A further significant increase from 62 percent to 91 percent occurred among males who smoked and used alcohol (x2 = 12.5, df= 1, p = 0.001). None of the female patients consumed alcohol. Therefore, it was not possible to study the association between alcohol and current caffeine intake in females.

Logistic Regression of Current Caffeine Intake.

Current caffeine intake was significantly associated with current smoking and alcohol use (table 3). None of the other independent variables were significant in the logistic regression, although the effect of typical neuroleptics was almost significant (table 3).

High Amount of Caffeine Intake in Caffeine

Consumers. In our sample, 38 percent (94/250) of patients had a high amount of caffeine intake. In the logistic regression within caffeine consumers, the only variable associated with a high amount of caffeine intake was current smoking (corrected OR = 3.8, Cl 11.5, 9.6], x2 = 8.1, df= 1, p < 0.01). The analyses of the median amount of caffeine intake for caffeine consumers in nonsmokers, non-heavy smokers, and heavy smokers suggested a dose effect: the median amount of caffeine intake was 1.3 mg/kg/day in nonsmokers, 2.7 in non-heavy smokers, and 3.4 in heavy smokers (Kruskal-Wallis was x2 = 23.1, df = 2, p < 0.001 for three populations, x2 = 10.3, df = 1, p = 0.001 for nonsmokers and non-heavy smokers; and x2 = 3.0, df = 1, p = 0.08 for non-heavy smokers and heavy smokers).

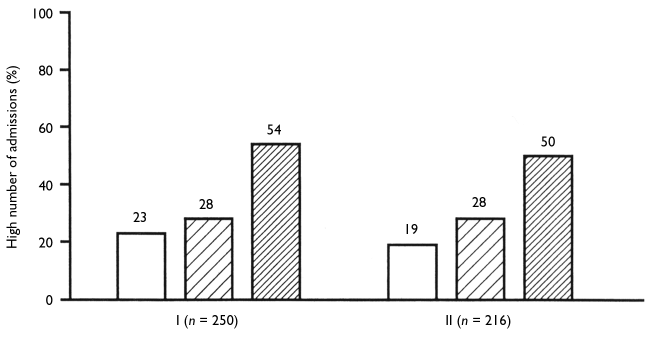

Caffeine Intake and Schizophrenia Symptomatology. Neither in the total sample nor in caffeine consumers was the amount of caffeine intake associated with scores in the 6 PANSS factors. All mean factor scores were very similar, and far from significant, when compared across high, non-high, and null amount of caffeine intake. The correlations between factor scores and the amount of caffeine intake were not significant and very low (r < 0.1). In the total sample, the nonsignificant correlation between the amount of caffeine intake and the total PANSS score was r = 0.04 (p = 0.6). In current caffeine consumers, the correlation was r = 0.02 (p = 0.9). Similarly, the amount of caffeine intake was not related to the historical prognosis measured by the number of hospitalizations, corrected by the illness duration. In current caffeine consumers who were taking antipsychotics, the nonsignificant correlation between amount of caffeine intake and dose of antipsychotic medication was r – 0.1 (p = 0.2).

Amount of Caffeine Intake and Nicotine Dependence. An attempt was made to xplore whether nicotine dependence might have an effect on the amount of affeine intake independent from the metabolic effect in the liver of smoking. In the 173 smokers, the FIND was significantly correlated with the amount of caffeine intake (r = 0.24, p = 0.002). The metabolic effects of smoking may explain this correlation. As a matter of fact, the significance of the correlation disappeared when controlling for the daily number of cigarettes (partial r = 0.04, p – 0.6). The correlation between the amount of caffeine intake and the FTND Morning Smoking factor (possibly a measure of nicotine dependence independent of heavy smoking) was r = 0.09 (p = 0.2). In summary, both analyses suggest that in smokers, the association between the amount of caffeine intake and nicotine dependence may simply reflect that more dependent smokers smoke more cigarettes, have greater CYP1A2 induction, and therefore may need a higher amount of caffeine intake to deliver caffeine to their brains.

Discussion

Association Between Caffeine Intake and Smoking. Current caffeine intake was associated with current tobacco smoking. Smoking also appeared to have an increasing metabolic effect. Heavy smokers appear to consume more caffeine than non-heavy smokers; nonheavy smokers consume more caffeine than nonsmokers. Once the metabolic effect of smoking was controlled for, nicotine dependence in smokers did not appear any longer to be associated with caffeine intake. Association Between Caffeine and Alcohol Intake. Current caffeine intake was related to current alcohol intake. This was a male effect. In males, the frequency of current caffeine consumers increased with smoking and further increased with alcohol consumption. This complex interaction among current caffeine intake, tobacco smoking, and alcohol use may or may not be present in the general population but has not been appropriately examined by studies investigating the three substances simultaneously (Istvan and Matarazzo 1984).

Lack of Association Between Caffeine Intake and Schizophrenia Symptomatology. The severity of schizophrenia symptomatology was not significantly associated with current caffeine intake or the amount of caffeine intake. This finding appears to be in agreement with three of five prior studies (table 2). The two other studies did not control for confounding effects of smoking, which is associated with caffeine intake.

Because of the cross-sectional nature of our study, it is not possible to rule out that changes in caffeine intake may be associated with changes in schizophrenia symptomatology. Unfortunately, longitudinal studies have not provided clear answers. In a double-blind study, Lucas and Pickar (1990) found that caffeine increased psychotic symptoms in 13 schizophrenia patients in spite of the antipsychotic treatment. Four studies compared the effects of switching from caffeinated to decaffeinated beverages (DeFreitas et al. 1979; Koczapski et al. 1989; Zaslove et al. 1991a; Mayo et al. 1993). In 14 U.S. male long-term inpatients (12 with schizophrenia), the switch to decaffeinated coffee was associated with a decrease in hostility and suspiciousness, and the improvement was reversed when caffeinated coffee was reintroduced (DeFreitas et al. 1979). In 33 Canadian schizophrenia inpatients, 4-week periods of decaffeinated coffee did not consistently improve behavior when alternated with 4- week periods of caffeinated coffee for 16 weeks (Koczapski et al. 1989). In a double-blind crossover study of 26 long-stay English schizophrenia patients there were no changes when patients were switched to decaffeinated beverages (Mayo et al. 1993). In a 1,200- bed U.S. State hospital, the ban of the sale of caffeinated beverages appeared to be associated with a decrease in assaultive behavior (Zaslove et al. 1991a). Due to the lack of control of other variables, it is possible that the decrease in assaultive behavior may reflect other hospital changes (Carmel 1991).

Lack of a Clear Association Between Caffeine Intake and Antipsychotic Treatment. In our study, neither current caffeine intake nor the amount of caffeine intake among caffeine consumers was significantly associated with a presence of extrapyramidal side effects or high doses of antipsychotic medication (typical antipsychotics had an effect in the border of significance in some analyses).

Comparison With the Spanish General Population. Unfortunately, systematic surveys of caffeine intake in Spain are scarce, so comparisons of our patients with the general population are limited. Two areas of Spain conducted systematic and representative health surveys of the population (Anitua and Aizpuru 1996; Jane et al. 2002). These area surveys (Gonzalez-Pinto et al. 1998; Jane et al. 2002) and a national survey (Pinilla and Gonzalez 2001) provide data on tobacco smoking but no data on caffeine intake. After an extensive computer search and inquiring in several universities, only two caffeine surveys could be identified. One included a control group of 1,086 subjects for a study of bladder cancer (Escolar-Pujolar et al. 1993). The other survey was performed by a consumer organization and has very limited data posted in a Web page (Organizaci6n de Consumidores y Usuarios [OCU] 2002). According to these surveys, 60 percent of the Spanish population consumed coffee at least once daily (Escolar-Pujolar et al. 1993) and 66 percent consumed coffee in the previous month (OCU 2002). In our sample, 49 percent (123/250) of patients reported to consume coffee daily and 51 percent (127/250) in the previous month. Caffeinated sodas were consumed by 45 percent of Spaniards in the previous month (OCU 2002). In our sample, 14 percent (36/250) reported to consume caffeinated sodas daily and 23 percent (58/250) in the previous month.

In our sample, 38 percent of patients had a high amount of caffeine intake (> 2 cups of coffee or 200 mg of caffeine/day). In the available Spanish surveys, 27 percent (Escolar-Pujolar et al. 1993) and 24 percent (OCU 2002) of Spaniards had more than two cups of coffee per day. However, these surveys did not measure other caffeinated beverages.

Conclusions

To conclude, this study suggests that in schizophrenia both current caffeine intake and amount of caffeine intake in caffeine consumers may be associated with tobacco smoking. Thus, the apparently excessively high intake of caffeine in schizophrenia patients reported in the literatura may reflect the well-known large percentage of smokers and heavy smokers in schizophrenia patients. In males, current caffeine intake was also significantly associated with current alcohol intake. Current alcohol intake and current smoking may have some kind of interaction, since among male smokers, the prevalence of current caffeine intake was higher among current alcohol drinkers tan among non-current drinkers. In caffeine consumers, a high amount of caffeine intake was not significantly associated with current alcohol intake. Another conclusion of this study is that neither current caffeine intake nor the amount of caffeine intake was significantly associated with the severity of schizophrenia symptomatology, not even after controlling for alcohol or tobacco use. However, owing to the cross-sectional nature of our data, we still cannot rule out the possibility of an association between caffeine intake and schizophrenia symptomatology. Longitudinal studies have to be carried out to address this issue. This is the first systematic survey of caffeine intake in schizophrenia patients that simultaneously takes into account smoking, alcohol intake, and schizophrenia symptomatology. New studies using repeated plasma caffeine levels in patients with schizophrenia and controls will also be needed to better investigate the above observations.

References

American Psychiatric Association. DSM-IV: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Washington, DCAPA, 1994.

Anitua, C, and Aizpuru, F. Encuesta de la Salud Publica. Vitoria, Spain: Servicio de Publicaciones del Gobierno Vasco, 1996.

Arias-Horcajadas, R; Padfn-Calo, J.J.; and Ferndndez- Gonzalez, M.A. Consumo y dependencia de drogas en la esquizophrenia. Adas Luso-Espanolas de Neurologia Psiquiatria y Ciencias Afines, 25:379-389, 1997.

Arias-Horcajadas, F.; Sanchez-Romero, S.; and Padi’n-Calo, J.J. Influencia del consumo de drogas en las manifestaciones clfnicas de la esquizofrenia. Adas Espanolas de Psiquiatria, 30:65-73, 2002.

Barnes, T.R.E. A rating scale for drug-induced akathisia. British Journal of Psychiatry, 154:672-676, 1989.

Barone, J.J., and Roberts, H.R. Caffeine consumption. Food and Chemical Toxicology, 34:119-129, 1996.

Bedate, H. Farmacos psicoestimulantes. In: Esplugues, J., ed., Perspedivas Terapeuticas con su Fundamento Farmacologico-Sistema Nervioso Central. Valencia, Spain: Fundacion Garcia Mufioz, 1981. pp. 199-219.

Benowitz, N.L. Clinical pharmacology of caffeine. Annual Review of Medicine, 41:277-288, 1990.

Benowitz, N.L.; Hall, S.M.; and Modin, G. Persistent increase in caffeine concentrations in people who stop smoking. British Medical Journal, 298:1075-1076, 1989.

Benson, J.I., and David, J.J. Coffee eating in chronic schizophrenia patients. American Journal of Psychiatry, 143:940-941, 1986.

Bertz, R.J., and Granneman, G.R. Use of in vitro and in vivo data to estimate the likelihood of metabolic pharmacokinetic interactions. Clinical Pharmacokinetics, 32:210-258, 1997.

Carmel, H. Caffeine and aggression. Hospital and Community Psychiatry, 42:637-638, 1991.

Carrillo, J.A.; Herraiz, A.G.; Ramos, S.I.; and Benitez, J. Effects of caffeine withdrawal from the diet on the metabolism of clozapine in schizophrenia patients. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology, 18:311-316, 1998.

Casas, M.; Prat, G.; Robledo, P.; Barbanoj, M.; Kulisevsky J.; and Jane, F. Methylxanthines reverse the adipsic and aphagic syndrome induced by bilateral 6-

hydroxydopamine lesions of the nigrostriatal pathway in rats. Pharmacology, Biochemistry, and Behavior, 66:257-263, 2000.

Cheeseman, H.J., and Neal, M.J. Interaction of chlorpromazine with tea and coffee. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 12:165-169, 1981.

Dalack, W.; Healy, D.; and Meador-Woodruff, J.H. Nicotine dependence in schizophrenia: Clinical phenomena and laboratory findings. American Journal of Psychiatry, 155:1490-1501, 1998.

De Freitas, B., and Schwartz, G. Effects of caffeine in chronic psychiatric patients. American Journal of Psychiatry, 136:1337-1338, 1979.

de Leon, J.; Dadvand, M.; Canuso, C ; White, A.O.; Stanilla, J.; and Simpson, G.M. Schizophrenia and smoking: An epidemiological survey in a state hospital.

American Journal of Psychiatry, 152:453—455, 1995.

de Leon, J.; Dadvand, M.; Canuso C; Odom-White A.; Stanilla J.; and Simpson G.M. Polydipsia and water intoxication in a long-term psychiatric hospital. Biological Psychiatry, 40:28-34, 1996.

de Leon, J.; Diaz, F.J.; Rogers, T.; Browne, D.; Dinsmore, L.; Ghosheh, O.; Dwoskin, L.P.; and Crooks, P. A pilot study of plasma caffeine concentrations in a U.S. simple of smokers and non-smokers volunteers. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry, 27:165-171,2003.

de Leon, J.; Tracy, J.; McCann, E.; and McGrory, A. Polydipsia and schizophrenia in a psychiatric hospital: A replication study. Schizophrenia Research, 57:293-301, 2002a.

de Leon, J.; Tracy, J.; McCann, E.; McGrory, A.; and Diaz, F.J. Schizophrenia and tobacco smoking: A replication study in another U.S. psychiatric hospital. Schizophrenia Research, 56:55-65, 2002fo

de Leon, J.; Verghese, C; Tracy, J.; Josiassen, R.; and Simpson, G.M. Polydipsia and water intoxication in psychiatric patients: A review of the epidemiological literature. Biological Psychiatry, 35:408^19, 1994.

Dixon, D.A.; Fenix, L.A.; Kim, D.M.; and Raffa, R.B. Indirect modulation of dopamine D2 receptors as potential pharmacotherapy for schizophrenia: I. Adenosine agonists. The Annals of Pharmacotherapy, 33:480-488, 1999.

Donovan, J.L., and DeVane, C.L. A primer on caffeine pharmacology and its drug interactions in clinical pharmacology Psychopharmacology Bulletin, 35:30-48, 2001.

El-Guebaly, N., and Hodgins, D.C. Schizophrenia and substance abuse: Prevalence issues. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 37:704-710, 1992.

Escolar-Pujolar, A; Gonzalez, C.A.; Lopez-Abente, G.; Errezola, M.; Izarzugaza, I.; Nebot, M.; and Riboli, E. Bladder cancer and coffee consumption in smokers and non-smokers in Spain. International Journal of Epidemiology, 22:38-44, 1993.

Ferre, S. Adenosine-dopamine interactions in the ventral striatum. Implications for the treatment of schizophrenia. Psychopharmacology, 133:107-120, 1997.

Ferre, S.; Herrera-Marschitz, M.; Grabowska-Anden, M.; Casas, M.; Ungerstedt, U.; and Anden, N.E. Postsynaptic dopamine/adenosine interaction: II. Postsynaptic dopamine agonism and adenosine antagonism of methylxanthines in short-term reserpinized mice. European Journal of Pharmacology, 192:31-37, 1991.

First, M.B.; Spitzer, R.L.; Gibbon, M.; and Williams, J.B.W. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (Clinician Version). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 1994.

Freedman, R.; Coon, H.; Myles-Worsley, M.; Orr-Urtreger, A.; Olincy, A.; Davis, A.; Polymerpoulos, M.; Holik, J.; Hopkins, J.; Hoff, M.; Rosenthal, J.; Waldo, M.C.; Reimherr, F.; Wender, P.; Yaw, J.; Young, D.A.; Breese, C.R.; Adams, C; Patterson, D.; Adler, L.E.; Kruglyak, L.; Leonard, S.; and Byerley, W. Linkage of a neurophysiological deficit in schizophrenia to a chromosome 15 locus. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 94:587- 92,1997.

Furlong, F.W. Possible psychiatric significance of excessive coffee consumption. Canadian Psychiatric Association Journal, 20:577-583, 1975.

Gonzalez, M.A. Consumo y dependencia de drogas en la esquizophrenia. Adas Luso-Espanolas de Neurologia Psiquiatria y Ciencias Afines, 25:379-389, 1997.

Arias-Horcajadas, F.; Sanchez-Romero, S.; and Padi’n- Calo, J.J. Influencia del consumo de drogas en las manifestaciones clfnicas de la esquizofrenia. Adas Espanolas de Psiquiatria, 30:65-73, 2002.

Barnes, T.R.E. A rating scale for drug-induced akathisia. British Journal of Psychiatry, 154:672-676, 1989.

Barone, J.J., and Roberts, H.R. Caffeine consumption. Food and Chemical Toxicology, 34:119-129, 1996.

Bedate, H. Farmacos psicoestimulantes. In: Esplugues, J., ed., Perspedivas Terapeuticas con su Fundamento Farmacologico-Sistema Nervioso Central. Valencia, Spain: Fundacion Garcia Mufioz, 1981. pp. 199-219.

Goff, D.C.; Henderson, D.C.; and Amico, E. Cigarette smoking in schizophrenia: Relationship to psychopathology and medication side effects. American Journal of Psychiatry, 149:1189-1194, 1992.

Gonzalez-Pinto, A.; Gutierrez, M.; Ezcurra, J.; Aizpuru, F; Mosquera, F; Lopez, P; and de Leon, J. Tobacco smoking and bipolar disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 59:225-228, 1998.

Haddock, C.K.; Lando, H.; Klesges, R.C.; Talcott, G.W.; and Renaud, E.A. A study of the psychometric and predictive properties of the Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence in a population of young smokers. Nicotine and Tobacco Research, 1:59-66, 1999.

Hamera, E.; Schneider, J.K.; and Deviney, S. Alcohol, cannabis, nicotine, and caffeine use and symptom distress in schizophrenia. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 183:559-565, 1995.

Hays, L.R; Farabee, D.; and Miller, W. Caffeine and nicotine use in an addicted population. Journal of Addictive Disorders. 17:47-54, 1998.

Heatherton, T.F.; Kozlowski, L.T.; Frecker, R.C.; and Fagerstrom, K.O. The Fagerstrom test for nicotine dependence: A revision of the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire. British Journal of Addiction, 86:1119-1127, 1991.

Hettema, J.M.; Corey, L.A.; and Kendler, K.S. A multivariate genetic analysis of the use of tobacco, alcohol, and caffeine in a population based sample of male and female twins. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 57:69—78, 1999.

Hirsch, S.R. Precipitation of antipsychotic drugs in interaction with coffee or tea. [Letter]. Lancet, 2:1130-1131, 1979.

Hughes, G.V., and Boland, F.J. The effects of caffeine and nicotine consumption on mood and somatic variables in penitentiary inmate population. Addictive Behaviors, 17:447^57, 1992.

Hughes, J.R. What alcohol/drug abuse clinicians need to know about caffeine. American Journal of Addiction, 5:49-57, 1996.

Hughes, J.R., and Howard, T.S. Nicotine and caffeine use as confounds in psychiatric studies. Biological Psychiatry, 42:1184-1185, 1997.

Hughes, J.R.; McHugh, P.; and Holtzman, S. Caffeine and schizophrenia. Psychiatric Services, 49:1415-1417, 1998.

Hughes, J.R., and Oliveto, A.H. A systematic survey of caffeine intake in Vermont. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 5:393-398, 1997.

Hyde, A.P. Response to «Effects of caffeine on behavior of schizophrenic inpatients.» Schizophrenia Bulletin, 16(3):371-372, 1990.

Istvan, J., and Matarazzo, J.D. Tobacco, alcohol and caffeine use: A review of their interrelationships. Psychological Bulletin, 95:301-326, 1984.

Jane, M.; Salto, E.; Pardell, H.; Tresserras, R.; Guayta, R.; Taberner, J.L.; and Salleras, L. Prevalencia del fumar en Cataluna (Espaiia), 1982-1998: Una perspectiva del genero. Medicina Clinica, 118:81-85, 2002.

Kim, D.S., and Palmiter, R.D. Adenosine receptor blockade reverses hypophagia and enhances locomotor activity of dopamine-deficient mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 100:1346-1351,2003.

Kirubakaran, V. Hyponatremic coma and elevated serum creatine phosphokinase following excessive caffeine intake. Psychiatric Journal of the University of Ottawa, 11:105-106,1986.

Koczapski, A.; Paredes, J.; Kogan, C; Ledwidge, B.; and Higenbottam, J. Effects of caffeine on behavior of schizophrenia inpatients. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 15:339-344, 1989.

Koczapski, A.B.; Ledwidge, B; Paredes, J; Kogan, C; and Higenbottam, J. Multisubstance intoxication among schizophrenia inpatients: Reply to Hyde. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 16:373-375,1990.

Kruger, A. Chronic psychiatric patients’ use of caffeine: Pharmacological effects and mechanisms. Psychological Reports, 78:915-923, 1996.

Lasswell, W.L., Jr; Weber, S.S.; and Wilkins, J.M. In vitro interaction of neuroleptics and tricylic antidepressants with coffee, tea, and gallotannic acid. Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences, 73:1056-1058, 1984.

Leibenluft, E.; Fiero, PL; Bartko, J.J.; Moul, D.E.; and Rosenthal, N.E. Depressive symptoms and the self-reported use of alcohol, caffeine, and carbohydrates in normal volunteers and four groups of psychiatric outpatients. American Journal of Psychiatry, 150:294-301, 1993.

LLerena, A.; de la Rubia, A.; Penas-Lledo, E.M.; Diaz, F.J.; and de Leon, J. Schizophrenia and tobacco smoking in a Spanish psychiatric hospital. Schizophrenia Research, 60:313-317,2003. Lucas, P.B.; Pickar, D.; Kelsoe, J.; Rapaport, M.; Pato, C; and Hommer, D. Effects of the acute administration of caffeine in patients with schizophrenia. Biological Psychiatry, 28:35^0, 1990.

Marcus, P., and Snyder, R. Reduction of comorbid substance abuse with clozapine. [Letter]. American Journal of Psychiatry, 152:959, 1995.

Mayo, K.M.; Falkowski, W.; and Jones, C.A. Caffeine: Use and effects in long-stay psychiatric patients. British Journal of Psychiatry, 162:543-545, 1993.

Mikkelsen, E.J. Caffeine and schizophrenia. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 39:732-736, 1978.

Missak, S.S. Exploring the role of an endogenous caffeinelike substance in the pathogenesis of schizophrenia. Medical Hypotheses, 36:157-161, 1991.

Olincy, A.; Young, D.A.; and Freedman, R. Increased levels of nicotine metabolite cotinine in schizophrenia smokers compared to other smokers. Biological Psychiatry, 42:1-5, 1997.

Organization de Consumidores y Usuarios (OCU). Cafeina: Uso y abuso. OCU-Salud, 41:9-12, 2002.

(htpp://www.ocu.org/publicacion/pdf/os_cafeina.pdf). Pares M; Munoz, L.; and Obiols, J.E. Consumo de cafe y tabaco y sintomatologia positiva y negativa en la esquizofrenia. Psiquiatria Biologica, 3:119-124, 1996.

Peralta, V., and Cuesta, M. Psychometric properties of the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) in Schizophrenia. Psychiatry Research, 53:31^0, 1994.

Pinilla, J., and Gonzalez, B. Profile of the population of Spain with respect to the smoking habit, period 1993-1997. European Journal of Public Health, 11:346-351, 2001.

Pontieri, F.E.; Tanda, G.; Orzi, F.; and Di Chiara, G. Effects of nicotine on the nucleus accumbens and similarity to those of addictive drugs. Nature, 382:255-257, 1996.

Rihs, M; Muller, C; and Baumann, P. Caffeine consumption in hospitalized psychiatric patients. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 246:83-92, 1996.

Schneier, F.R., and Siris, S.G. A review of psychoactive substance use and abuse in schizophrenia: Patterns of drug choice. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 175:641-652, 1987.

Shoaib, M; Swanner, L.S.; Yasar, S.; and Goldberg, S.R. Chronic caffeine exposure potentiates nicotine self-administration in rats. Psychopharmacology, 142:327-333, 1999.

Simpson, G.M., and Angus, J.W.S. A rating scale for extrapyramidal side effects. Ada Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 212(Suppl): 11-19, 1970.

Swanson, J.A.; Lee, J.W.; and Hopp, J.W. Caffeine and nicotine: A review of their joint use and possible interactive effects in tobacco withdrawal. Addictive Behaviors, 19:229-256, 1994.

Test, M.A.; Wallisch, L.S.; Allness, D.J.; and Ripp, K. Substance use in young adults with schizophrenia disorders. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 15:465-76, 1989.

Van Ammers, E.C.; Sellman, J.D.; and Mulder, R.T. Temperament and substance abuse in schizophrenia: Is there a relationship? Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 185:283-288, 1997.

White, A.O., and de Leon, J. Clozapine levels and caffeine. [Letter]. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 57:175-176, 1996.

Winstead, D.K. Coffee consumption among psychiatric inpatients. American Journal of Psychiatry, 133:1447-1450, 1976.

Zaslove, M.O.; Russell, R.L.; and Ross, E. Effect of caffeine intake on psychotic in-patients. British Journal of Psychiatry, 159:565-567, 1991a.

Zaslove, M.O.; Beal M.; and McKinney, R.E. Changes in behaviors of inpatients after a ban on the sale of caffeinated drinks. Hospital and Community Psychiatry, 42:84-85, 19916.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to patients and staff of the Granada-South and Granada-North Community Mental Health Centers and their outpatient rehabilitation unit for their collaboration and to Institutional Review Boards of the San Cecilio and Virgen de las Nieves University Hospitals who approved this protocol. We wish to thank Juan Rivero, R.N., who works at the Granada-Sur Mental Health Center, for his help with data collection and Margaret T. Susce, R.N., M.L.T., who works at the Mental health Research Center at Eastern State Hospital, Lexington, KY, for her help with editing of this article. M. Carmen Aguilar’s work in this study was supported by a grant from the Spanish Agency for International Cooperation (A.E.C.I.). Dr. Diaz was partially supported by a grant from the Dirección de Investigaciones de la Universidad Nacional, Medellin, Colombia.

The Authors

Manuel Gurpegui, M.D., is affiliated with the Department of Psychiatry and Institute of Neurosciences University of Granada, Granada, Spain, in a position that would be equivalent to U.S. Associate Professor. M. Carmen Aguilar, M.D., rotated through the Department of Psychiatry and Institute of Neurosciences, University of Granada, Granada, Spain, in a position that would be equivalent to a U.S. psychiatry fellowship. This study was part of her doctoral dissertation (an academic requirement in Spain for physicians who want to extend their training). Jose M. Martinez-Ortega, M.D., is a doctoral student for the doctoral program for physicians at the Institute of Neurosciences, University of Granada, Granada, Spain. Francisco J. Diaz, Ph.D., is affiliated with the Department of Statistics, Universidad nacional, Medellin, Colombia, in a position that is equivalent to U.S. Associate Professor. Jose de Leon, M.D., is Medical Director, Mental Health Research Center, Eastern State Hospital, Lexington, KY.

* Estimado lector, este es un blog de divulgación científica dirigido al profesional, estudiante, y en general, a toda persona interesada en el campo de la psiquiatría. La información aquí expuesta, no constituye una recomendación para que usted realice ningún tipo de tratamiento médico o psiquiátrico, ni sustituye la visita a un especialista. Ante cualquier patología, consulte siempre a un profesional de la medicina o de la psiquiatría.